W3C Customer Experience Data Specification Released

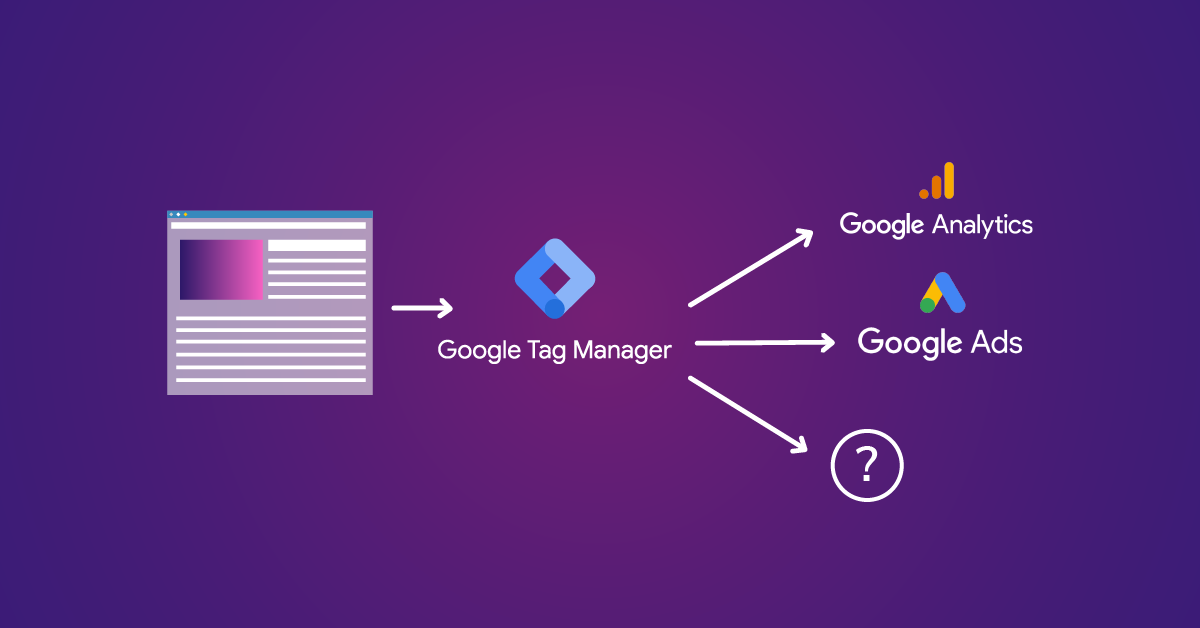

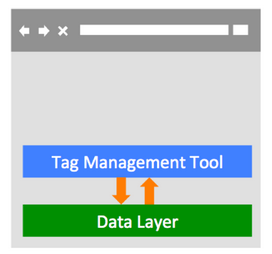

If you use Google Tag Manager or another tag management tool, you’re probably already familiar with the idea of a data layer. It’s basically a centralized place for information about the page to be passed to analytics and other measurement tools.

Up to now, there have been some informal conventions in tools like GTM. But it would help us all to have some standard guidelines, for interoperability between tools. So, if you need to switch from one tool to another, you can easily do that without rearranging the data. Or, if you build a plugin for a content management system, you can build to the standard and not worry about which tool it will be used with.

So a W3C Community Group was assembled to tackle this problem, including 56+ organizations (including Google Tag Manager) providing input on a specification that is standardized enough to provide interoperability, without being too rigid to represent many different industries and websites. (LunaMetrics also participated in the development of the specification.)

After much deliberation, version 1.0 of this specification has been published. Let’s take a look at what it says and does.

Specification

The specification (pdf link) essentially defines some naming conventions, and all that it asks is that, if you use the spec, you use the names it puts forward. (You’re also free to add additional information; a discussion of extensibility is below.)

The standard is based on a JavaScript object named digitalData that contains heirarchical data about the website and the customer experience.

The digitalData object can contain sub-objects with information about a number of different aspects of the customer experience:

page: information about the page itself, potentially including things such as the URL, referrer, title, and categorizationproduct: information about one or more products represented in the contentcart: representing products that someone has added to a shopping carttransaction: like cart data, but after the purchase is completedevent: other interactions that take place within the pagecomponent: content components of the pageuser: data about the users themselves

Within each of these sub-objects, data is represented by name-value pairs or “properties”. Some of the names are reserved, meaning that the name is always used in a standard way. You can also add other optional pieces of information using the extensibility mechanism.

Here’s one example:

digitalData = {

pageInstanceID: "ProductDetailPageNikonCamera-Staging",

page:{

pageInfo:{

pageID: "Nikon Camera",

destinationURL: "http://mysite.com/products/NikonCamera.html"},

category:{

primaryCategory: "Cameras",

subCategory1: "Nikon",

pageType: "ProductDetail"},

attributes:{

Seasonal: "Christmas"}

},

product:[{

productInfo:{

productName: "Nikon SLR Camera",

sku: "sku12345",

manufacturer: "Nikon"},

category:{

primaryCategory: "Cameras"},

attributes:{

productType: "Special Offer"}

}]

};

The names in blue are reserved names, that hold special meaning in the specification (and you can read the details to get the guidance on what they are intended for, but most of them are pretty obvious). There’s also some information here in grey, which represent non-reserved naming: things you can add to make the data best represent your site. Let’s take a look at the options for that.

Extensibility

The specification provides extensibility in several ways:

- Add new properties. For example, maybe you have a travel site, so in the

productobject above, maybe instead ofskuormanufactureryou need properties likeoriginAirportanddestinationAirport. As long as you avoid the reserved names, you can add these to existing objects. In addition, all objects contain anattributessub-object that doesn’t reserve any names — you can put any properties in there you want. - Add new objects. You can add entirely new objects if you need to record data that doesn’t fit into any of the existing ones. Maybe you’re in the healthcare industry, and you need to capture information about each

memberof an insuranceplan.

Both of these examples are explored in the specification object, and as the specification gets tried out in wider use, I’m sure plenty of industry-specific examples will be generated.

Privacy & Security

The more data we put in this data layer, the more careful we need to be about what tools have access to which data. (The specification document has an appendix that has lots of great information in it about the security and privacy issues you should consider.) This specification creates a way to do that with objects called privacy and security.

Basically, the privacy object allows you to specify a set of access categories and which tools get access to each category. The security objects allow you to specify, for each piece of information in the data layer, which categories it belongs to.

Note that the specification itself doesn’t have any way to enforce these privacy and security preferences. You need a third party tool (like, potentially, your tag management system) to actually enforce these. The specification simply allows you to express those preferences for such a tool.

Go forth and conquer data

In some ways, you can see the publication of this specification as the end of a long process of collaboration between many organizations, and it is.

But like all specifications, the old adage applies: “The proof of the pudding is in the eating.” There is much still to be learned and refined as the specification is implemented across diverse websites and toolsets.

For your part, there’s no rush to rename elements of your data layer right now if it’s already working for you. But there are a few things you can do:

- As you move forward and revise your data layer or add additional elements, consult this specification and stick with standardized naming where possible.

- Ask and encourage your tool vendors to support this specification.

- Provide feedback about the specification, including (a) notes on aspects that don’t work as expected, are missing, etc. – it’s a 1.0 and it’s not perfect; and (b) contributing industry-specific examples and naming conventions.

You can provide your input on the W3C Community Group wiki.

Last of all, a big thanks to all the participants in the development, but especially to Viswanath Srikanth of IBM, who led this effort and really kept it moving forward toward the finish line.